Explanation and icon by iconographer Randi Maria Sider-Rose

The icon called Anastasis (ah-NAH-sta-sis), or The Resurrection, is a symbolic depiction of Christ’s descent into Hades in order to redeem humanity. He is grasping the hands of Adam and (usually) Eve, who represent all men and women awaiting their Savior. It is the moment of Christ’s ultimate degradation, and yet the beginning of his glory. He stands in a blue and white almond “mandorla,” a symbolic shape suggesting the passageway between two worlds, also to be found in icons of the Nativity and Transfiguration.

But in the Anastasis the two worlds collide: Christ, in new white garments with gold rays issuing forth like the rays of dawn, crashes down through the cliffs into the dark abyss. His hands are pulling Adam and Eve out of their caskets and his feet “trample down death by death,” on the doors to Hell. A figure representing death, or perhaps the prince of darkness himself, is bound and crushed beneath the criss-crossed gates. Satan is surrounded by broken instruments of bondage and torture: nails, handcuffs, wrenches, and the like.

Often there are more people in the Anastasis icon, representing the people who came before Christ, historically speaking, who are also redeemed. Behind Adam stand figures of the Old Testament: Kings David and Saul, as well as others. John the Baptist often stands on this side too, gesturing towards Christ as if to say, “Behold, the lamb.” On the other side, behind Eve, are the un-named masses, awaiting their Savior.

Other Icons Related to the Resurrection

The deliverance of people from Hades is a major theme of Great Saturday, a theme which runs through and is inseparable from Pascha:

Thou hast descended into the abyss of the earth, O Christ, and hast broken down the eternal doors which imprison those who are bound, and, like Jonah after three days inside the whale, Thou hast risen from the tomb. (Irmos of Ode 6 of the Paschal Canon, cx. Acts 2:14-39, 1 Peter 3:19)

The image of Jonah was actually the first way the Resurrection was depicted in iconography. The image of the historic event of the women bearing spices and approaching the empty tomb also dates back to at least the third century (the Church in Dura Europos).

In all three of these modes of depiction, the precise moment and manner of resurrection remains a mystery, unlike the visible event of the resurrection of Lazarus.

Read More

How Easter got its name: Bede was wrong. The English word for Pascha doesn’t come from the name of a pagan goddess. So where does it come from?

Celebrating Pascha: The Queen and Lady of Days: The great celebration of Pascha stands alone, outside any list, and outside of time itself.

Pascha for families with disabilities: The Pascha midnight service is glorious, but it can be hard for families that include children (or parents!) who have disabilities or special needs. Here are some ideas to help.

Randi Maria Sider-Rose is the iconographer of Immanuel Icons, an Orthodox Christian iconography studio in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

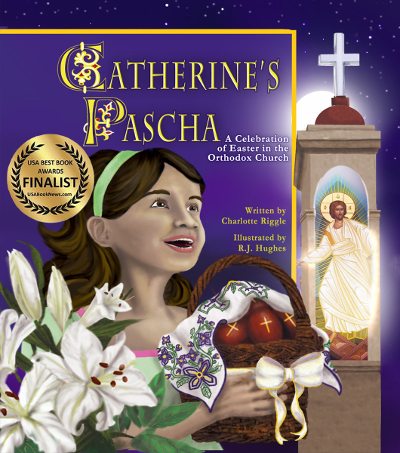

Books by Charlotte Riggle

Catherine’s Pascha shares the joy of Pascha through the eyes of a child. Find it on Amazon or Bookshop.org.

![]()

The Saint Nicholas Day Snow is filled with friendship, prayer, sibling squabbles, a godparent’s story of St. Nicholas, and snow. Lots and lots of snow. Find it on Amazon or Bookshop.org.

![]()

In The Grace of Being There, women who are, or have been, single mothers share stories of their relationships with saints who were also single mothers. Charlotte’s story of the widow of Zarephath highlights the virtue of philoxenia. Find it on Amazon or Park End Books.