Part 1 of a two-part guest post by Nicole Roccas, PhD

When I initially wrote Time and Despondency, I didn’t expect that one of the biggest groups to express interest in the topic of despondency would be parents concerned for their children. Yet, in the months since sending out copies to advance readers of the book, the folks who’ve consistently had the most pressing questions were parents. They want to know if children suffer from despondency, and if so, how they can recognize it and help them.

Admittedly, these are tough questions for me–I have neither children nor any professional qualifications to render me an expert on them. Instead, I am benefited by my own childhood experiences of despondency and a freakishly keen memory. I have also been aided by friends’ and acquaintances’ observations of their children, which have helped me realize my experiences were not exceptional.

In this post, I first explain what despondency is before sharing a childhood experience of it. Stay tuned for the follow-up post, in which I’ll discuss how we can relate helpfully, honestly, and lovingly to children about of despondency.

What is Despondency?

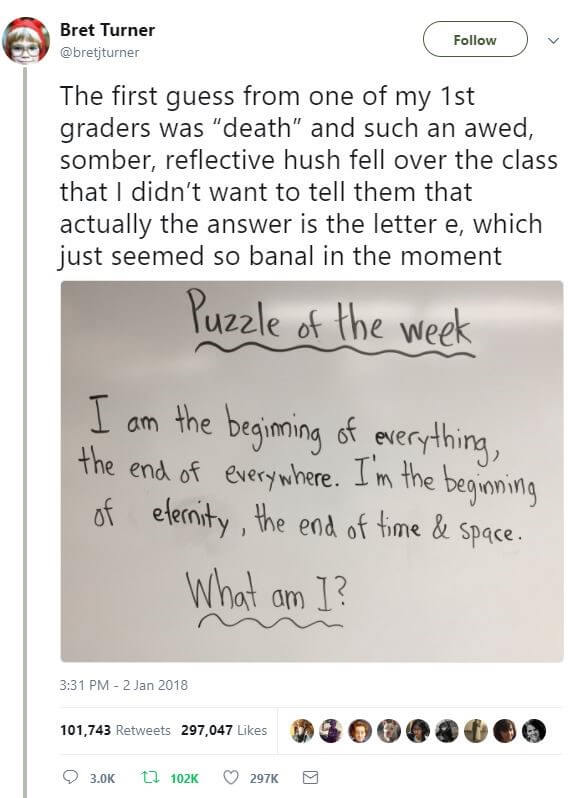

I should start by saying that despondency is complex once you actually start digging into it. This infographic distills my concept of the condition in a simple, visual way if the following discussion gets a little hard to navigate.

Despondency has countless symptoms: anxiety, restlessness, distractibility, hopelessness, irritability, and fatigue are among them. If you’re thinking this sounds a lot like depression, you’re right–despondency and depression do share many characteristics in common. I’m not a medical professional, however, so I can only examine these concepts through a historical and theological lens. In doing so, I believe the two ailments–despondency and depression–are not direct equivalents. The concept of despondency emerged from the soul-centered vision of the human person that was prominent in early Christianity, clinical depression from the body-centered paradigm of modern Western medicine. Because of this, to treat the two as synonyms would be anachronistic. More importantly, though, it minimizes or muddles the contributions both theology and medicine have to make toward healing the human person. In short, if you’re depressed, my book will not cure that; but it may be helpful nonetheless to think and learn more about despondency, which has been on the spiritual roadmap of Christians for well over a millennium. (I explore this question in greater detail in Chapter 1 of Time and Despondency.)

Back to despondency. I’ve only explained the symptoms so far. What’s at the heart of this condition?

Describing despondency, ascetical theologians of early Christianity favored the Greek term akedia, which literally means an absence of care or concern–a kind of existential, soul-slackening boredom. They understood akedia as a lack of effort, especially in spiritual matters. This is different than apatheia, a kind of detachment from harmful passions and thoughts which the Fathers praised. In despondency, we fail to care about things we should care for–prayer, for example, or the well-being of our neighbor, or the state of our soul and interpersonal relationships.

What is the cause of this apathy? Evagrius, a fourth-century monk in the Nitrian Desert of Egypt, believed it was the contrary forces of anger and desire–anger at what we have, desire for what we do not have. For example, anger about the undesirable job you’re stuck in, endless distracting fantasies about a job you wish you had. These two currents harden the mind into a deadly stalemate, an intractable battle of dissatisfaction. That stalemate is the breeding ground for despondency. Unable to come to terms with our present circumstances, we retreat into carelessness, distraction, anxiety, procrastination, sleep, hopelessness, or other ruminative habits.

In her best-selling book Acedia & Me, Author Kathleen Norris roots despondency even further than the anger and desire Evagrius points out: in pain. We retreat into the anger/ desire of despondency when the wound of caring becomes to difficult or painful to bear. In this view, then, the “symptoms” of despondency I mentioned above are like coping mechanisms to deal with that pain. Distraction, sleep, boredom, restlessness, etc., become ways of avoiding or covering up the wounds of our existence.

Of the many sources of pain in our lives, the deepest and scariest is the knowledge of our mortality. As attested to by both modern psychology and ancient theology, the conscious or subconscious fear of death lies at the center of almost all our broken, destructive thoughts and habits. We are haunted, unavoidably, by the brevity and uncertainty of this life.

That’s despondency in a nutshell. It’s hardly an easy condition to talk about or wrap our minds around, much less face. But it’s real, and–for many of us–a regular facet of our lives. Which brings us to the question at hand…

Can children struggle with despondency?

My gut response to this question is: why not? Children are human beings, too. As such, they are not spared from the kinds of pain, anger, or desire that can give way to despondency.

If anything, perhaps children are more prone to the deep pain I mentioned above. They haven’t yet accumulated years of avoidance tactics or the shield of cynicism we adults use to ignore or self-medicate ourselves from the wound of existence.

It’s possible children face despondency more honestly and openly than we adults do. They haven’t yet accumulated years of avoidance tactics or the shield of cynicism we use to self-medicate ourselves from the reality of death.

The introduction of my book opens with experience from my own childhood, a conversation about death I had with my elementary school guidance counselor. At the time, I was beginning to understand that death is an actual thing, a reality that can and will affect me and my loved ones. Along with that came a newfound awareness of how fast time goes–life suddenly seemed frighteningly, paralyzingly short to me. The sting of all of this led me to feel cheated or betrayed. Until then, I’d been duped into falsely believing life was hopeful, bright, and unending.

We all go through that process of realization, that moment of clarity when we the weight and sting of death come into focus. For me, it was a confusing and circuitous journey to understanding. I often wondered if maybe I’d gotten it wrong–perhaps death didn’t exist. At any moment, I expected the guidance counselor “to assure me–as adults were fond of doing–that it would make sense when I was older, that death was just a misunderstanding” (page 12). What most confused me was that none of the adults around me (who, I assumed, were “in on the secret” of death) were crying all the time or endlessly lamenting the specter of death and the impermanence of life. On the contrary: they appeared to be living normal, well-adjusted lives, unconcerned about the dark reality of mortality.

This led my childhood mind to conclude that either a) they didn’t know what I did about death; or b) the conclusions I had reached concerning death were wrong and there was no reason to be alarmed.

As it turns out, though, I wasn’t too far off in my conclusions. Death is real. Life is brief. And yes, that is sad–deeply sad.

Recalling my childhood thought process now half a century later, part of me can smile with recognition at my lifelong flair for melodrama and melancholy. But mostly, I am moved by how those early wrestling matches with death were deeply human, deeply transparent, and deeply real. I doubt my adult self could muster the same emotional honesty if I tried. While I still mourn the impermanence of life, somehow that trauma has been dulled by cares, distractions, or cynicism.

Then as now, all accounts indicate I was no stranger to despondency. Once I awakened to the reality of death as youngster, my mind was often shadowed by a cloud of hopelessness I can still feel on a visceral level today. Already in elementary school, I seriously wondered whether life was worth living in the face of my newly found knowledge.

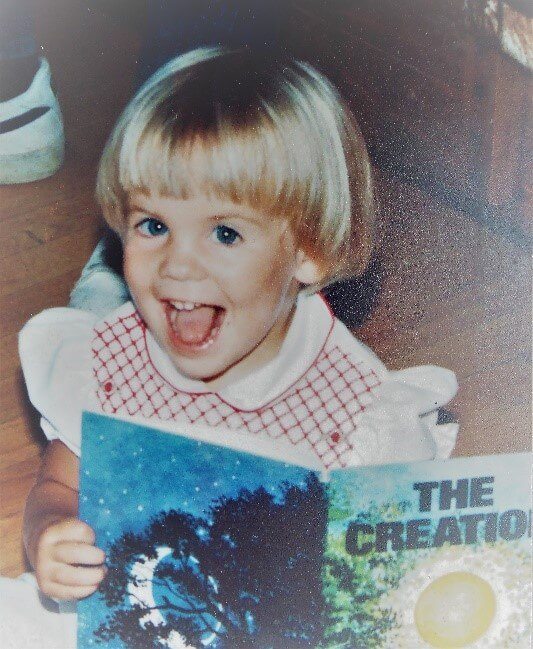

My most trusted refuge from this abyss was reading. Along with being my best friends, books were just plain fun. Or at least, that’s how I always pictured my grinning, book-loving, childhood self (see picture above). But while visiting home my first year of graduate school, I ran into my fourth-grade teacher (ironically, we bumped into each other at the library, mutual bibliophiles as we are!). She recognized me immediately and began sharing her surprisingly vivid memories of elementary-school Nicole. Among other things, she cited my erstwhile fondness for books. “You were always reading very serious and advanced books,” she reminded me, mentioning a title I had been particularly keen on at that age (Missing May, by Cynthia Rylant). Upon revisiting the book, which I only vaguely remembered, I discovered its themes revolved around grief, death, abandonment, and the afterlife. Go figure. Evidently, even my “fun” times as a kid were spent contemplating meaning, life, and death. How little I’ve changed!

All that to say, if my experience is any indication, children can and do struggle with despondency–perhaps even more profoundly or honestly than we adults do. In the next post, on February 4, I will discuss how we may recognize despondency in children (and in ourselves) and help them learn to face it from the vantage point of hope.

About the Author

Nicole Roccas, PhD, lives in Toronto and works as a freelance book editor at The Writer’s Loom. She is the author of Time and Despondency: Regaining the Present in Faith and Life (Ancient Faith Publishing). Find her on the Ancient Faith podcast and blog, Time Eternal, or on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram.

Read More

Time and Seasons: In the Orthodox Church, the day starts at sunset, the year starts in the fall, and life starts with death.

Stephen to Lazarus: A Poem by C.S. Lewis: In a brief poem, C.S. Lewis muses on the death of Lazarus, and what it meant for him to give up his death.

Sasha and the Dragon: A fairy tale with angels: Sasha is afraid that his grandmother will die. And he is afraid of the dragon that lives under his bead.

Buy the Books!

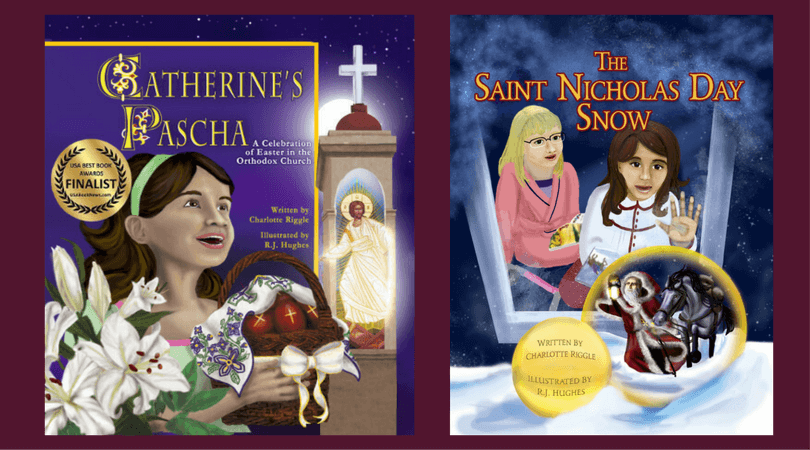

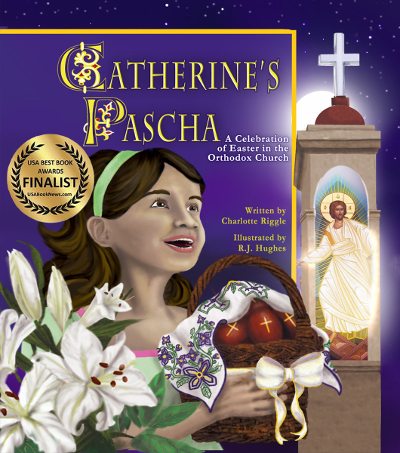

Catherine’s Pascha

FINALIST IN THE 2015 USA BEST BOOK AWARDS

Catherine doesn’t like vegetables. She doesn’t like naps. She doesn’t like it when her mom combs her hair. She loves hot dogs, chocolate cake, and her best friend, Elizabeth. Most of all, she loves Pascha! Pascha, the Orthodox Christian Easter, is celebrated in the middle of the night, with processions and candles and bells and singing. And Catherine insists that she’s not a bit sleepy.

Celebrate the joy of Pascha through the magic of a book: Catherine’s Pascha. Available on Amazon, Bookshop.org, and my webstore.

The Saint Nicholas Day Snow

Shoes or stockings? Horse or sleigh? Does St. Nicholas visit on December 6 or on Christmas Eve? Will a little girl’s prayer be answered? When Elizabeth has to stay at Catherine’s house, she’s worried about her grandmother, and worried that St. Nicholas won’t find her. The grownups, though, are worried about snow.

Celebrate the wonder of St. Nicholas Day through the magic of a book: The Saint Nicholas Day Snow. Available on Amazon, Bookshop.org, or my webstore.

Hi Nicole!

This is your fourth grade teacher, here! I’m so honored that you mention me in your article. I certainly remember you as an intelligent, deep-thinking nine year old. Do you remember the book Stone Fox by John Reynolds Gardiner? Your fourth grade small book group read it. When I asked your group of readers why Grandpa, in the story, couldn’t get out of bed for days on end, you answered, “Why! He must be depressed.” I was amazed that anyone your age would know about such things!

Keep up the wonderful work you do, Nicole!