In the sixth century, you don’t find many love stories. You might have found a love match among those who were free but poor. If neither you nor the other had anything to give or trade, then perhaps hearts could be given freely, wherever you chose. But we don’t know the stories of the poor.

The rich and powerful were a different matter. Marriages were political and commercial transactions. They bolstered trading relationships, secured alliances, removed competitors. What did love have to do with it?

And yet … and yet …

Theodora’s Beginnings

Theodora was the daughter of a bearkeeper at the circus. Her father died when she was five years old. Her mother remarried, and Theodora and her older sister worked as performers — actresses, entertainers, child prostitutes. She had a child, a daughter, when she was but fourteen herself. But Theodora was beautiful and talented, and enormously successful.

In spite of her success, though, Theodora wanted something different. She left her career to serve as mistress to an important and powerful man. But she didn’t stay with him long. She ended up fleeing to the desert, and finding shelter with the ascetic communities in Syria. Those were Monophysite communities, whose beliefs about the nature of Christ put them at odds with the Orthodox church in Constantinople.

Nevertheless, after some time in Syria, she returned to Constantinople. It was her home, but her options there were limited. She didn’t want to return to her career as an entertainer. As a former actress, she couldn’t marry. Eventually, she was able to take up work as a woolspinner.

Justinian’s Beginnings

When Justinian was born, his father, a farmer, named him Flavius Peterus Sabbatius. And Flavius expected to be a farmer like his father, until his uncle Justin called him to Constantinople. Justin provided his nephew with an education, treated him as a trusted advisor, and when he became emperor, he named Flavius — now known as Justinian — his heir.

Justinian was fifteen years older than the woolspinner whose shop he must have passed from time to time. He was one of the most important men in Constantinople. He could have whatever he wanted — including women.

But he wanted to marry Theodora, the woolspinner, the mother of an illegitimate child, the bearkeeper’s daughter.

The Impossible Becomes Possible

The Emperor Justin’s wife was Euphemia, a woman whose background was not all that dissimilar from Theodora’s. When Justinian asked Justin to change the law so that he could marry Theodora, Justin may have found the request amusing. He could have demanded that his heir choose a more suitable wife. Instead, he changed the law.

This act had many, many consequences. First, of course, it allowed Justinian and Theodora to marry. When they married, it was traditional for the groom to give lavish gifts to his bride. Theodora knew what people whispered: that she cared only for power and money. She also knew that men might make promises and fail to keep them. So she asked that Justinian give her one thing, and one thing only — a small house that would be her property, irrevocable. It was a place she could retreat to when the gossip was too much for her. And, although she doubtless never said this out loud, it was a place she could retire to if Justinian ever abandoned her for another woman.

This change in law also put it into Theodora’s mind that the most important thing that could be done to protect women was to change the laws that bound women to immorality and servitude. After Justinian became emperor, he took as his most important work a complete reworking of the Roman law. Justinian and Theodora worked together on this project, as they did on many projects. Theodora ensured that the Justinian Code gave women rights and protections they had never had. Under the new laws, daughters inherited with their brothers, widows retained control of their dowries, the daughters of slaves were not slaves, actresses were allowed to change their profession, pimping was illegal, and brothels were closed. Once the brothels were closed, Theodora created a refuge for former prostitutes, so they would have a place to live. She named the refuge Metanoia, which means Repentance.

A Marriage of Equals

Theodora’s name, of course, means Gift of God, and Justinian always referred to her as “my gift.” But he didn’t use diminutives and endearments to belittle her. At his coronation, he named her his co-ruler. And that wasn’t an empty title. She had her own court, and (to the dismay of certain powerful men) her own budget. She worked with Justinian on many of his most important projects. He valued her ideas, and he respected her position. This made her many enemies — men (and even a few women) who felt that she didn’t belong in their circles. Indeed, the main source of information about her comes from a man named Procopius, who hated her with every fiber of his being.

But Justinian recognized that his young wife was as brilliant and as powerful as he was. More than that, he knew she was tough. That was a quality he lacked, and he valued it in his wife. During the Nike Revolt, when the city was rioting, Justinian’s closest advisors urged him to flee. Theodora sent him a brief note: The imperial purple makes a fine burial shroud. Justinian understood the message, and stayed. The riots were put down. He, and his empire, survived.

And so in spite of — or maybe because of — her toughness, Justinian, and indeed everyone close to her, adored her. Although duplicity was the political currency of the time, her entire court was intensely loyal to her. There was never, during her reign, a single case of a member of her court accepting a bribe or engaging in a plot against her. Instead, those who worked for her honored her and protected her from schemes and threats of every sort.

Matters of the Church

Along with his military campaigns and his work on the legal code, Justinian also saw it has his duty to try to heal the breach in the Church between the Monophysites and the Orthodox. Perhaps, if it weren’t for Theodora and her love for the Monophysites who had sheltered her, if it weren’t for his love for Theodora, he might have used force against the Monophysites. He certainly had advisors who wanted him to. Instead, he chose to work towards mutual understanding, with respect. As part of these negotiations, he wrote a hymn about Christ in terms that were acceptable both to the Monophysites and to the Orthodox:

Only Begotten Son and Immortal Word of God,

Who for our salvation didst will to be incarnate of the holy Theotokos and ever virgin Mary,

Who without change didst become man and wast crucified, O Christ our God,

Trampling down death by death, Who art one of the Holy Trinity,

Glorified with the Father and the Holy Spirit, save us.

Justinian commanded that this hymn be sung during every Divine Liturgy. It was, and it still is, in every Orthodox Church, to this very day.

The Enduring Love of Justinian and Theodora

Justinian and Theodora had not yet been married 25 years when Theodora became ill. The exact nature of the illness isn’t clear, although it seems likely that it was breast cancer. She died and was buried in the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. In the years that followed, Justinian would visit her tomb to light candles and pray for her.

One of Justinian’s last great projects, one of the very few he accomplished after Theodora’s death, was the building of the monastery fortress of St. Catherine in Sinai. The desert climate has been kind to the buildings there. The monastery church still has its original wooden door, which closes on its original pins and hinges. The roof still rests on the original sixth century beams. One of the beams bears an inscription regarding the most pious emperor Justinian and his late empress Theodora.

Theodora never retired to the little house that had been her wedding gift. She had no need to. Justinian loved only her, to the end of his life.

Read More

The Story of Peter and Fevronia: Peter, the Prince of Muron, married the peasant woman Fevronia. The nobles tried to end the marriage, but Peter chose exile with his wife. The feastday of Ss. Peter and Fevronia is now celebrated as the Day of Love.

The Mystery of our Holy Mother Anastasia: Anastasia was one of the women in Theodora’s court. What was she afraid of?

Books by Charlotte Riggle

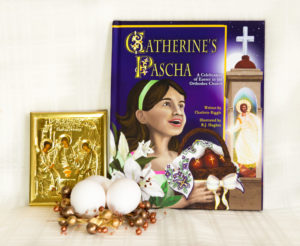

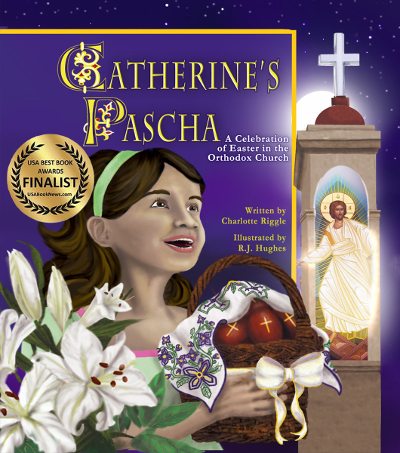

Catherine’s Pascha shares the joy of Pascha through the eyes of a child. Find it on Amazon or Bookshop.org.

![]()

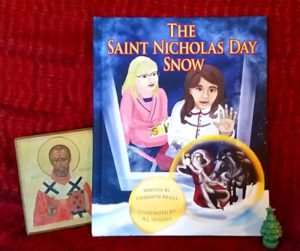

The Saint Nicholas Day Snow is filled with friendship, prayer, sibling squabbles, a godparent’s story of St. Nicholas, and snow. Lots and lots of snow. Find it on Amazon or Bookshop.org.

![]()

In The Grace of Being There, women who are, or have been, single mothers share stories of their relationships with saints who were also single mothers. Charlotte’s story of the widow of Zarephath highlights the virtue of philoxenia. Find it on Amazon or Park End Books.

Theodora – a heroine for the ages

Indeed she is!

So cool!!!!!!!!! 😀

Thank you. I admire Theodora. No disrespect… named one of my pugs after her