I once heard a homily for the Sunday of the Prodigal Son, in which the priest explained that the parable is dangerous. We might be tempted to see in the father the example of a loving parent. But any parent that, in real life, acted as the father of the prodigal son was doing it wrong. That father wasn’t truly loving, the priest explained; that father was weak and indulgent.

The story of the Prodigal Son

The younger son comes to the father and says, “I want my inheritance now.” Which is rather like saying, “I care more about your money than I care about you; it doesn’t matter to me whether you live or die.” And the father gives him his inheritance. He doesn’t lecture or yell. He doesn’t kick him out. He doesn’t disown him. He just does as his son asks.

And then the son goes away. We don’t know why he left. Maybe his father’s rules were too strict. Maybe he couldn’t manage to be the son he thought his father wanted. He didn’t know how to be like his older brother, the responsible one. Maybe his mother had recently died, and he couldn’t bear to be in the house without her.

Whatever the reason, he found living in his father’s house too much to bear. Whatever the reason, he takes his money, and he leaves. He goes to a far country, where he starts blowing all his money on parties and prostitutes.

The prodigal son returns

Eventually, the younger son runs out of money. He has spent every last coin he had on prostitutes and parties. He finds himself in such a bad state that he’s in danger of starving. And because he is hungry, he decides to go home. There is no indication that he recognizes that he’s done anything wrong, or that he wants to see his father again. But he knows he won’t survive where he is. He needs the safety of his father’s house.

He memorizes a little speech, calling himself out as a sinner. That, he hopes, will persuade his father to give him food and shelter.

And so he turns his steps toward home. And all this time, his father has been watching for him. He sees him coming, runs out to meet him. He embraces him. He ignores his son’s stupid speech. He knows it’s a lie. But it doesn’t matter. His son that was dead is now alive. He’s home.

The father doesn’t ask anything of his son. He doesn’t demand to know what happened to the money. He doesn’t ask if he’s done consorting with prostitutes. He doesn’t need to know any of that. His son is alive. He’s home.

The prodigal son’s older brother

The prodigal son’s older brother is pissed. He’s always done the right thing. He’s always served his father. And his father has the audacity to welcome his wastrel brother like visiting royalty.

So, just as the younger son left, the older son refuses to come in.

And just as the father ran out to greet his younger son, he goes out to meet his older son. He doesn’t close the door against him. He meets his son where he is.

Is this a dangerous story?

The priest whose homily I remember from so long ago said that the father of the prodigal was a terrible father, and the story was a dangerous story. It might lead us to indulge our children’s every whim. It might lead us to believe that God doesn’t care what we do with the blessings he showers on us.

Was he right?

Do we need a companion story, one that teaches us tough love? One that reminds us that it’s okay to love the sinner, as long as we make it clear that we hate their sin?

No. Never.

Jesus told us this parable because he wanted us to know that God’s love for us is not based on anything we do. We can’t be good enough to make him love us more, because he loves us with everything that he is. We can’t be bad enough to make him love us less. What we do is honestly and utterly irrelevant. He loves us because we’re his children, his sons and daughters, his beloved ones.

He wants us to know that what St. Paul told us is true: Neither death nor life, nor angels nor principalities nor powers, nor things present nor things to come, nor height nor depth, nor any other created thing, can ever separate us from the love of God.

Perhaps that kind of love, God’s love, really is dangerous.

If you love in this way, you won’t just love people you approve of. You’ll love everyone who comes across your path, without considering whether they deserve your love or not. After all, God makes the sun rise on the evil and the good; he sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous alike.

What should we do?

When the prodigal’s father saw his younger son’s half-hearted, self-serving repentance from afar, he ran to him, to bring him the rest of the way home. When he saw his older son’s anger and fear, he didn’t wait even for self-serving repentance. He went to his son, to invite him to come in. Not because he was weak and indulgent. But because, in the strength of his love for his children, he wanted them to be with him.

Just like God wants us to be with him.

Like the father of the prodigal son, God won’t prevent us from walking away from him. He won’t make us come in. But if we want to be with him, he’ll come out to meet us, in whatever condition we’re in. He won’t wait for us to be good before he loves us. He won’t wait for us to love him before he loves us. He never turns us away. He never closes the door against us.

If you believe that people are naturally inclined towards evil, if you believe that you must threaten them or force them to be good, that kind of love might well seem dangerous.

And perhaps it is. Because that kind of love, it seems to me, is the most powerful force in all of creation.

Use it well.

Read More

Christine, who fasted during the fast-free week: The fast-free weeks are always joyful. But Christine kept a perpetual fast, not from piety, but from poverty.

When Jesus was the guest of Zacchaeus the Publican: It’s easier to understand the lessons of the Sunday of the Pharisee and the Publican when you understand who the publicans were.

How to love strangers: Lessons in philoxenia: The Church teaches us to defeat evil by cultivating the corresponding virtue. And one of the most important virtues is philoxenia — love of the stranger.

Buy the Books!

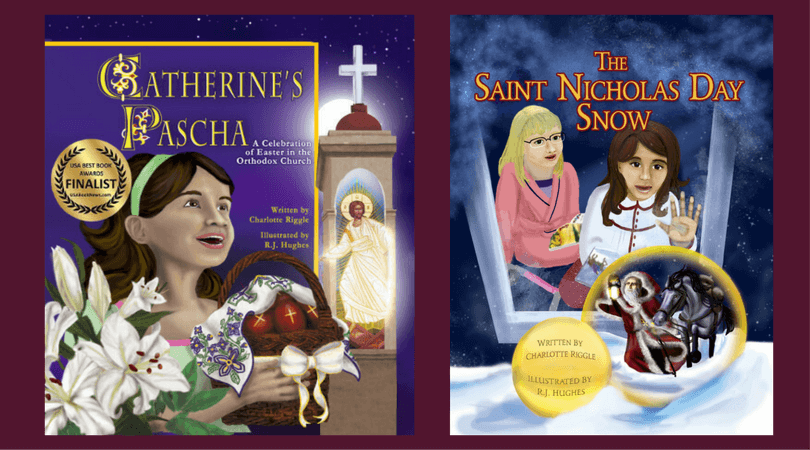

These delightfully diverse books provide disability representation (Elizabeth, one of the main characters, is an ambulatory wheelchair user). They also give Orthodox Christian children the rare opportunity to see themselves in books, and children who are not Orthodox the chance to see cultural practices they may not be familiar with.

Catherine’s Pascha

FINALIST IN THE 2015 USA BEST BOOK AWARDS

Catherine doesn’t like vegetables. She doesn’t like naps. She doesn’t like it when her mom combs her hair. She loves hot dogs, chocolate cake, and her best friend, Elizabeth. Most of all, she loves Pascha! Pascha, the Orthodox Christian Easter, is celebrated in the middle of the night, with processions and candles and bells and singing. And Catherine insists that she’s not a bit sleepy.

Celebrate the joy of Pascha through the magic of a book: Catherine’s Pascha. Available on Amazon, Bookshop.org, and my webstore.

The Saint Nicholas Day Snow

Shoes or stockings? Horse or sleigh? Does St. Nicholas visit on December 6 or on Christmas Eve? Will a little girl’s prayer be answered? When Elizabeth has to stay at Catherine’s house, she’s worried about her grandmother, and worried that St. Nicholas won’t find her. The grownups, though, are worried about snow.

Celebrate the wonder of St. Nicholas Day through the magic of a book: The Saint Nicholas Day Snow. Available on Amazon, Bookshop.org, or my webstore.