St. Gorgonia was born in Nazianzus, Cappadocia, in the early part of the fourth century. She was the daughter of St. Gregory the Elder and St. Nonna and the sister of St. Gregory Nazianzen and St. Caesarius. She had at least two sons, along with three daughters, whose names were Alypiana, Eugenia, and Nonna. She died sometime between 369 and 374.

All we know of St. Gorgonia comes from the funeral oration that her brother, St. Gregory, delivered. Gorgonia’s household would have included dozens if not hundreds of enslaved people. They would have come from all parts of the known world, serving as accountants, doctors, tutors, weavers, cooks, companions, and more. St. Gregory mentioned none of them. Yet it seems to me that they would have had much to say about St. Gorgonia’s life and holiness. What follows, then, is the story of St. Gorgonia as they might have told it.

In the atrium

Gorgonia was dead and buried. Her husband, Alypius, was still in his seat in the atrium, where he had collapsed when he returned from the funeral. Servants had brought a small table and filled it with plates of wine and cheese and figs and olives drizzled with honey. Alypius drank the wine but ate nothing.

Bishop Gregory, Gorgonia’s brother, gave up any thought of sleeping. He rose and stepped out of the bedchamber. The snow had stopped, the sky cleared, and the moon, just past full, brought enough light into the atrium that he had no need for a lamp.

He stood still for a moment, as still as the statues of heroes and kings that stood around the space, as still as the painted garden on the walls behind them. It seemed that the fountain was the only thing that moved, and it filled his mind with thoughts of the mourners dancing and weeping at his sister’s funeral.

He shook his head and moved a chair so that he could sit near Alypius. A servant filled a goblet for him. He picked up a fig and stared at it a while before eating it. He said nothing. Everything he wanted to say, he had said at Gorgonia’s funeral.

In the attic

The moonlight that filled the courtyard didn’t make it into the attic room where the women servants slept. There were no windows, and there was, of course, no brazier. The heat from their bodies and the thick straw on the floor was enough to keep them warm. A single lamp gave just enough light that the women could avoid tripping over each other as they came and went.

There was no danger of tripping over the oldest of the kitchen maids; she was in her corner, snoring loudly. The other kitchen maids, exhausted from serving the funeral meal, had settled near her. They seemed to be asleep.

Koritsáki slipped in and let her eyes adjust to the dim light. She saw where the weaver had made herself a nest in the straw. “Koritsáki,” the weaver said softly, “That you, Koritsáki? Why you not with Alypania? She need you tonight, with her mother dead and buried.”

“It’s me,” Koritsáki responded. “Alypania said she wanted to be alone to weep for her mother, and she sent me away. I told her I could make a bed in the hall outside her bedchamber, in case she needed me, but she said no.”

The seamstress and the weaver shifted to make room for Koritsáki between them. She laid down and shifted the straw underneath her.

A household divided

“Weaver, do you remember when I was brought here?” Koritsáki asked.

“I remember,” she said, and Koritsáki could hear a smile in her voice. “Despota went away, on trip to Nazianzus. In Nazianzus, he marry Despoina. We not know Despoina when he brought her here. We not know about Christians. Despoina was only Christian in household. That caused uproar, first morning Despoina here, when she not honor household gods.”

“Despoina, she didn’t want anyone else to honor them, either,” said the seamstress. “Despoina wanted Despota to destroy the idols.”

“She did. Despota said he agree that she not worship household gods. He not agree that rest of household not worship household gods. He most surely not agree to destroy household gods. Despota and everyone in household except Despoina would worship household gods. So Despoina went to slave market later. At slave market, she buy every Christian slave there. Including you, Koritsáki. She tell Despota that her Christian slaves not worship household gods either.”

The matter of names

“The only thing I remember about that day,” said Koritsáki, “is that I called Despoina by her name. I called her Gorgonia. I heard Despota call her that. I was so young, and only newly enslaved, and I didn’t know that I couldn’t call her by her name. So I called her Gorgonia, and the next thing I knew, Despoina was holding me in her arms, weeping and praying for me.”

“I was there,” said the weaver. “I saw what happen. I saw manservant strike you for insolence. You collapse on floor, and we all thought he kill you. We thought you dead, Koritsáki. Despoina pick you up from floor. She hold you, she call you her koritsáki, her little girl. She beg God to let you live.”

“It was different then, before Despoina came,” the seamstress said. “Despota, he ruled the household with blows and anger. Despoina, she said that God did not rule that way, and she would not allow it. She would not allow anyone to lay a hand on her or her slaves or anyone in the household who worshipped her God.”

“That why slaves join Despoina for prayers,” said the weaver. “First Christian slaves, then more slaves. Pretty soon, all household slaves pray with Despoina. Most still honor household gods, too, at first. But if we pray with Despoina, she not allow anyone to beat us or whip us.”

“Not even Despota,” the seamstress said. “Not even him.”

There was a long silence, then the oldest kitchen maid gasped, rolled over, and began snoring again.

Gorgonia’s funeral

“You sleep now, Koritsáki?” asked the weaver. “Can you tell about funeral?”

Koritsáki had been staring at the lamp, lost in her thoughts. She took a deep breath. “I’m awake,” she said. “I can tell you about the funeral. Did you see it when it began?”

“No,” said the weaver. “I working with young wardrobe maid. We repairing clothes that Despoina’s mother tore when Despoina’s soul left body.”

Koritsáki nodded. “The undertaker arranged her body on the bier, so that it looked like she was reclining at the table. She was as pale as marble, because Bishop Gregory did not allow the undertaker’s servant to put makeup on her face. He said she never wore makeup in life, and he would not have her beauty defiled by it in death.

“The singers and mourners stood in the street while they waited for the bier to be brought out of the house. The snow had already started falling; big, fat flakes drifted down like feathers. When the door opened, the mourners began keening and singing and dancing and walking toward the tombs. The men carrying the bier followed them, and then Despota and Despoina’s brother and her parents, and then everyone else of the household.

“When we got to the tombs, the men took the bier into the church and set it in front of the altar. The rest of us crowded in, and Bishop Gregory and Bishop Faustinus served the Liturgy.”

The funeral oration

“After the Liturgy,” Koritsáki continued, “Bishop Gregory told us all about Despoina’s life.”

“He say anything you not already know?” asked the weaver.

Someone across the room hissed and said, “Hush, you. That’s enough. I want to sleep.”

“I too sad to sleep. So, Koritsáki, tell more about funeral.”

“Yes,” said the seamstress. “Koritsáki, tell us more.” There was silence, except the sound of mice in the straw and the old woman’s snoring.

“Just speak soft so old ones sleep,” said the weaver.

“I’ll speak as soft as death,” said Koritsáki. “After we received the holy mysteries, and the prayers were done, Bishop Gregory stood up to speak. He explained why it was fitting for him to speak, instead of our own Bishop Faustinus. Then he talked about their parents. Oh, did you know? I didn’t know this. Their mother taught their father to be a Christian, just like Despoina taught Despota to be a Christian, before they were baptized together.”

“I not know this,” said the weaver. “Is strange thing indeed, that Christian man would give his daughter to pagan man.”

“Bishop Gregory said many strange things,” said Koritsáki. “He said Despoina was both a maiden and a wife, but that didn’t make any sense to me. She bore five children, did she not?”

“She did,” said another voice in the darkness. “Five that lived. I was there for all of them.”

The reason for Gorgonia’s modesty

“After that, he talked about her modesty, and the way she would smile but never laugh. That’s true enough. I don’t think I ever heard her laugh. Did you?”

There were murmurs of “no, nor I” from all around.

“Let me think a moment,” said Koritsáki. “He praised Despoina for so many things. He said she never wore gold nor jewels, nor painted her face, and she never had her hair done in spiral curls or fancy styles.”

“Oh, I know why Despoina not wear hair in fancy curls,” said the weaver. “Her brother Caesarius said why, last time he visit, before he die.”

“What did he say?” asked Koritsáki.

“He ask Despoina if she remember when they young. He remind her when he and Gregory see her getting hair done up all in fancy curls. They tell her fancy curls were snakes. They tell her she not their sister. She Gorgon. Even her name say she Gorgon. She monster. They make her cry.”

“They didn’t!” said Koritsáki.

“Caesaria say they did,” said the weaver. “He say that why she always wear hair so plain. She wear hair so she not look like Gorgon. And Despoina, she remember, and she not cry. She smile.”

“Imagine that,” said Koritsáki. “Bishop Gregory said she wore her hair plain because she was so modest.”

“That is the truth,” said the seamstress. “Despoina, she had much modesty. But it was the teasing that made her choose modesty.”

Koritsáki thought for a moment. “She kept choosing that, too, didn’t she. She never changed her mind about it.”

Hospitality, prayer, and fasting

“Bishop Gregory said she chose to be hospitable, too. We’ve all seen that, every one of us, because we all have had more work to do because of it.”

There were murmurs of agreement. “After that, he talked for a long time about how she fasted, and kept watches in the night, and chanted the psalms, and prayed more than anyone.”

The oldest of the kitchen maids turned in her bed, snorted and coughed, then lapsed back into quiet snores.

An accident and what came after

Koritsáki rubbed her eyes. Talking made it easier not to cry. “He told us a couple of stories about Despoina, too. One of them we all knew, but the other one, it was the strangest of all the things Bishop Gregory said.”

“Tell us strange story first,” said the weaver.

“No,” said the seamstress, “Tell us the story we know first, and then tell us the new story.”

“That’s what Bishop Gregory did,” said Koritsáki. “He told us first about the time that she was out in her carriage, and the mules bolted, the carriage overturned, and she was dragged and nearly killed.”

“Oh, yes, I remember,” said the weaver.

“He talked about how some of the people who saw the accident were unbelievers, and they knew she believed that God intervenes in the lives of the righteous. They said that, if she were righteous, she wouldn’t have had such an accident. So Despoina, stern lady that she was, told the doctors to go away. Since God allowed the accident, God would have to provide the cure.”

“I thought she would die,” said the wardrobe maid. “I think we all did. But God listened to her and healed her.”

“Yes,” said the weaver, “and some unbelievers who saw accident, and saw healing, some of them became believers.”

A second story of healing

“After Bishop Gregory told that story, he asked Bishop Faustinus for permission to tell another story. It was a story they both knew, but they had never told anyone else.”

“Did Bishop Faustinus say he could tell story?” asked the weaver.

“He did. Bishop Gregory reminded us of the time, just a few years ago, when Despoina had been so terribly sick. Do you remember? Her raging fevers made her as helpless as a baby. She lapsed into comas, until we all thought she would die. But then she’d have spells where she seemed to be getting better, until the fever started again. Bishop Faustinus thought she was ready to leave this life. Then, suddenly, she was well.”

“I remember,” said the weaver.

“I remember, too,” said the seamstress. “So many doctors, they came in and out of the house, tending to her. So many people, they were praying for her. Nothing made a difference for long.”

Koritsáki nodded. “Bishop Gregory said that on the last night of her illness, she was doing a little bit better, feeling a little bit stronger, and she managed to get herself to the chapel. She went straight to the altar, and she leaned on it, calling on God to heal her as he had done before. She cried so many tears with her prayers that there was a puddle of tears on the altar.”

“Wasn’t she afraid? What if Bishop Faustinus had come in?” asked the wardrobe maid.

“I think she was only afraid of dying,” said Koritsáki. “But there’s more. After she was done crying, she took the chalice with the reserved mysteries, and she mixed them with her tears, and she anointed her body all over with the mysteries and the tears, as if it were chrism at a baptism.”

“She didn’t!” said the wardrobe maid.

“Despoina, she not do that!” said the seamstress.

“Oh, Seamstress,” said Koritsáki, “everyone at the funeral must have thought the same, the way they gasped and murmured. But Bishop Gregory said that after she anointed herself, she was at once healthy and whole and full of joy, and she walked back to her chamber, and the illness was completely gone.”

A longed-for death

“But still she died,” said the weaver, “and so young.”

“Bishop Gregory said that she wanted to die,” said Koritsáki, “so she could be with God. He said that God told her the day she would die, so that she would be ready for it.”

“The rest of us had to get ready, too,” said the wardrobe maid. “Despota ordered the sarcophagus and rose water and spices. Cook ordered everything for the funeral feast. Weaver and I made the cloth for her bier, and Seamstress and I embroidered it with roses and violets.”

“The cloth is so beautiful,” said Koritsáki. She wiped her eyes. “So, on Despoina’s last day, she went to bed, and told her husband and their children and everyone else whatever she needed to tell them. That much I know is true, because Alypania spent the afternoon that day with Despoina, and listened to Despoina’s instructions.”

“All her family was there,” said another of the women, “and Bishop Faustinus, too.”

The last kiss

“Her parents and her brother had arrived a few days before,” said Koritsáki, “and when we all thought she had died, and her mother had given her the last kiss, Bishop Faustinus noticed that she was still breathing, and her lips were moving. He leaned in close, and heard her whispering, over and over, ‘I will lay me down in peace, and take my rest.’ Then she went silent, and her soul went to be with God.

“That was the end of Bishop Gregory’s oration. Then Despota picked up her body from the bier as if she were a baby, and he carried her from the church. It was still snowing, and one of the men removed the white cloth that had been keeping snow out of the sarcophagus. Despota laid her in the sarcophagus, as gently as could be, and he kissed her.”

Gorgons on the sarcophagus

“Koritsáki, you saw the sarcophagus. What did it look like?” asked the seamstress.

“The top was carved with garlands of roses and violets, just like the cloth you and Wardrobe Maid and Weaver made for the bier. It had peacocks and fountains and saints on the front, and it had Gorgons on the ends.”

“Why Despota choose sarcophagus with Gorgons?” asked the weaver.

“I don’t know,” said Koritsáki.

“I heard Bishop Gregory ask him that,” said a voice in the darkness. “He said all the sarcophagi from Prokonessos come with Gorgons, and there wasn’t time to order something else.”

“That may be true,” said the young wardrobe maid. “But I think he would have wanted the Gorgons anyway. I think he wanted them to guard Despoina’s journey to the next life.”

“Despota Christian,” said the weaver. “Despoina Christian. They no need Gorgons.”

“Despota sometimes still leaves offerings for the household gods,” said the wardrobe maid.

“Despoina know about offerings?” asked the weaver. “She know about Gorgons on sarcophagus? What she say?”

“I don’t think she knew,” said Koritsáki.

The end of the story

“But what about the funeral?” asked the seamstress. “That’s what I want to know. After Despoina was in the sarcophagus, what happened?”

Koritsáki thought for a moment. “There’s not much left to tell. After Despota kissed her, the women began keening and crying, and Bishop Gregory told them to stop. He told them to sing hymns and psalms as they came to the sarcophagus to kiss her. When everyone had given her a kiss, the men closed the sarcophagus. Alypania fainted, and her brother helped me bring her back to the house.”

“And that is the end of the story,” said a voice from the kitchen maids’ corner. “I will be up before cock crow, and I have heard enough. Now be quiet, you, and let me lay down in peace, and take my rest.”

“That is the end of the story,” said Koritsáki. She sighed deeply and shifted the straw under her. The old kitchen maid resumed snoring. Koritsáki wiped away a tear.

Prayer

Saint Gorgonia, daughter of Christian parents and mother of Christian children, mother and sister of bishops, salvation of a pagan husband, by your example you have taught us to keep the rules of prayer and hospitality. We entreat your prayers that we might likewise become holy and of benefit to our loved ones and to all who are in need, and that God, who healed you twice, will grant healing of soul and body to all who turn to you in faith.

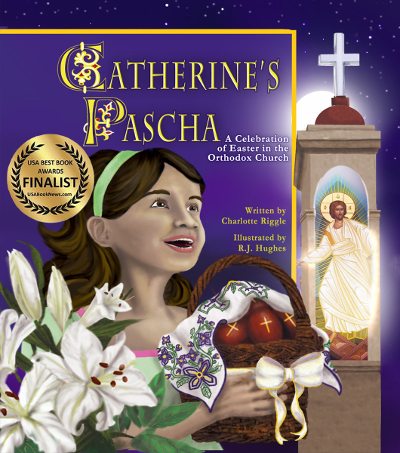

Books by Charlotte Riggle

These classic holiday picture books bring the joy of Pascha and the magic of Saint Nicholas Day to life. Find them on Amazon or Bookshop.org.

The Grace of Being There is a collection of essays by women who are, or have been, single mothers, sharing stories of their relationships with saints who were also single mothers. Charlotte’s story of the widow of Zarephath highlights the virtue of philoxenia. Find it on Amazon or the Park End Books website.