If you’re a reader, you know that writers often refer to characters and stories that came before them. Tolkein didn’t have to make up dragons from scratch. He expected that his readers would have read other stories about dragons, especially the dragon from Beowulf, and that they would bring what they knew about that dragon to his story, and apply it to his dragon. Likewise, Milton expected his readers to know the first few chapters of Genesis when they read Paradise Lost, and to bring what they knew to his story.

When I taught college English, I realized that my students often experienced literary allusions backwards. They read the new works first, then went back to the old writings. Their experience of Milton informed their understanding of Genesis, and their experience of Tolkein informed their understanding of Beowulf, rather than the other way around. As I learned to watch for backwards allusions, I began to notice the times I had experienced them myself.

First encounters

As best I can remember, I first met C.S. Lewis in Mere Christianity, and shortly after that, I discovered some of his academic writings. Later, when I had children of my own, I discovered Narnia, The Screwtape Letters, and the breathtakingly beautiful Til We Have Faces. It was much later when I read his Space Trilogy.

By that time, I had read a great deal of science fiction, exploring strange new worlds, encountering new lives and new civilizations. Yet I had encountered nothing like the middle book of that trilogy, Perelandra. On visiting Perelandra, I found a world filled with wonder and possibility and awe and astonishment all at once. The foundation of that world was the knowledge that you need seek nothing, that the good would come to you. All you had to do was embrace the wave that came.

Who was Dorotheos?

Years later, I encountered that world again when I was reading Dorotheos of Gaza: Discourses and Sayings. You’ve likely never heard of Abba Dorotheos. He was a monk and abbot of the monastery at Thawata, not far from the city of Gaza in the Palestinian desert. He lived in the sixth century, well after the time of the ascetics whom we know as the Desert Fathers. While you’ve likely never heard of Dorotheos, ascetics you’ve certainly heard of, St. Seridos, along with St. Barsanuphius and the Prophet John, were also at the monastery at Thawata when Dorotheos was there. You’ll learn more about all of them in the introduction of the book, which provides a richly detailed look into Dorotheos’s life and times.

During Dorotheos’s years at the monastery, he had many different roles. He wanted more than anything to be a hermit, but for many years his spiritual fathers didn’t allow it. He was for a time the infirmarer, and for a time the guest master. When he was finally permitted to become a hermit, he was given the responsibility of checking on the welfare of all of the hermits associated with the monastery. From time to time, the hermits would gather to share a meal and to listen to edifying discourses. These discourses were collected, and eventually found their way to my bookshelf.

Dorotheos and C.S. Lewis

As I read the first discourse, “On Renunciation,” I had the sudden realization that C.S. Lewis must have read Dorotheos. Dorotheos’s explanation of the power and importance of renunciation could easily be summed as, “embrace the wave that comes.”

Dorotheos explains that a monk must cut off his own desires. As he learns to do this, he discovers that “whatever happens to him he is satisfied with it, as if it were the very thing he wanted. And so, not desiring to satisfy his own desires, he finds himself always doing what he wants to. For not having his own special fancies, he fancies every single thing that happens to him.”

Dorotheos, of course, explained in detail how a monk could achieve this state. I am certain that Lewis read this and began to wonder what it would be like if you had lived always in this state and had never known any other. He explored this idea by creating, Tinidril, the Green Lady of Perelandra, whose every delight was the will of God, who had complete control over her own will, and who lived in utter joy, fancying every single thing that happened to her, embracing always the wave that comes.

Dorotheos and John Donne

I had the same experience when reading what is arguably one of the most famous poems in the English Language is “Valediction: Forbidding Mourning” by John Donne. This masterpiece works through a series of images that try to depict a couple’s love. The final image is that of a compass. I have sometimes wondered if Donne’s image was inspired by a passage from St. Dorotheos’s discourse, “On Refusal to Judge Our Neighbor.”

“Suppose we were to take a compass,” he says, “and insert the point and draw the outline of a circle. The centre point is the same distance from any point on the circumference. Now concentrate your minds on what is to be said! Let us suppose that this circle is the world and that God himself is the centre; the straight lines drawn from the circumference to the centre are the lives of men. To the degree that the saints enter into the things of the spirit, they desire to come near to God, and in proportion to their progress in the things of he spirit, they do in fact come close to God and to their neighbor. The closer they are to God, the closer they become to one another, and the closer they are to one another, the closer they become to God.”

Encountering Dorotheos and the Desert Fathers

I don’t think that Donne expected his readers to recognize the allusion to Dorotheos, and perhaps Lewis didn’t either. Yet if I had read Dorotheos first, before reading Perelandra, and before reading Donne, I would have brought more of Dorotheos’s ideas and ideals into my reading of their works. It would have created a richer experience – an experience I can recreate by going back and re-reading them after reading Dorotheos.

It’s the same with reading the Sayings of the Desert Fathers. In his discourses, Dorotheos quotes from them liberally, along with Scriptures and other writings he expected his audience to be familiar with. I read him long before I read the others. You don’t have to have read the Sayings first in order to appreciate the Discourses. If you fall in love with him first, as I did, you can always go back and read the Sayings, and then come back to him. When you do that, you’ll find his words even richer than you did the first time, as the Sayings enrich your experience of him.

Entry into paradise

If you’ve already read the Sayings, you’ll want to put Dorotheos next in your to-read stack. You’ll find his writings much more accessible than the Sayings, and more applicable to your own daily life.

Not always, though, because a monastic life is a Christian life. While there are differences in our callings, some things apply to all of us. You don’t need to be a monastic to take to heart every word of Dorotheos’s discourses, “On refusal to judge our neighbor” or “On falsehood.” In the former, he sets forth principles without limit; in the latter, he expounds on the importance of truth, and acknowledges the narrow limits where it is proper for a Christian to lie. In every case, he illustrates his discourses with stories and illustrations that make them memorable and (dare I say it?) even fun.

As with any writings intended for a monastic audience, though, sometimes you have to apply the principles differently if you’re not a monastic. For example, in his discourse “On consultation,” Dorotheos explains, “If it is my duty to get something done, I prefer it to be done with my neighbor’s advice, even if I do not agree with him and it goes wrong, rather than to be guided by my own opinion and have it turn out right.”

A monk may be able to apply this exactly as written. If you’re a physician, though, or a structural engineer, you absolutely can’t. Yet you can put this saying in the context of all that Dorotheos said. A physician or a structural engineer might not be able to let a mistake go by, but we can surely listen carefully and with humility to others. In doing this with diligence, and applying all the other advice that Dorotheos offers, we can “by the loving kindness of Christ, attain our entry into paradise itself by the prayers of all the saints. Amen.”

Read More

The Uncondemning Monk: We don’t know the Uncondemning Monk’s name, or much about him. Only that he was a lousy monk. And that he never judged anyone.

St. Moses the Black: How a murderous highway robber became an icon of humility and self-control.

In this family, we don’t judge: What I’ve learned about judging others from the lives of the saints.

Buy the Books!

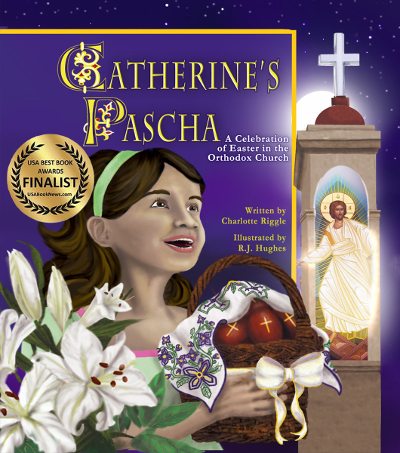

Catherine’s Pascha

FINALIST IN THE 2015 USA BEST BOOK AWARDS

Catherine doesn’t like vegetables. She doesn’t like naps, and she doesn’t like it when her mom combs her hair. She loves hot dogs, chocolate cake, and her best friend, Elizabeth. Most of all, she loves Pascha! Pascha, the Orthodox Christian Easter, is celebrated in the middle of the night, with processions and candles and bells and singing. And Catherine insists that she’s not a bit sleepy.

Celebrate the joy of Pascha through the magic of a book: Catherine’s Pascha. Available on Amazon, Bookshop.org, and my webstore.

The Saint Nicholas Day Snow

Shoes or stockings? Horse or sleigh? Does St. Nicholas visit on December 6 or on Christmas Eve? Will God answer a little girl’s prayer? When Elizabeth has to stay at Catherine’s house, she’s worried about her grandmother, and worried that St. Nicholas won’t find her. The grownups, though, are worried about snow.

Celebrate the wonder of St. Nicholas Day through the magic of a book: The Saint Nicholas Day Snow. Available on Amazon, Bookshop.org, or my webstore.