St. Alban was a soldier in the Roman army in Britain, perhaps when Diocletian was emperor, or perhaps when the emperor was Decius or Septimus Severus. Whenever it was – just after the year 200, or just after the year 300, or somewhere between – it wasn’t a good time to be a Christian.

That was okay, because Alban wasn’t a Christian. He was a pagan. He had a reputation for being a virtuous man. And, for the pagans, one of the most important virtues was philoxenia: hospitality towards strangers.

Stories of philoxenia

Alban undoubtedly knew the story of Baucis and Philemon. According to the story, Baucis and Philemon were an old married couple. They owned little, but when a couple of strangers presented themselves at their door, Baucis and Philemon offered them food and shelter, the best they could give. It wasn’t long before Baucis realized that their guests were not ordinary travelers. They were Hermes and Zeus. And because everyone else had turned them away, these gods destroyed the town around them. They made the hovel Baucis and Philemon lived in a temple, and granted them their wish that, when the end of their life came, they would die together.

That sort of story was common in years past, before greed was good. Lot and his wife entertained two strangers, who were revealed to be angels and who destroyed the surrounding town for inhospitality. And Paul spoke of the need to entertain strangers, for by doing so, he said, some had entertained angels without knowing it.

And it wasn’t just Mediterranean cultures. In the Russian fairy tale of Marco the Rich and Vasily the Unlucky, St. Nicholas and the Lord God disguise themselves as beggars to seek hospitality from Marco, who refuses them. As a result, Vasily ends up receiving everything that had been Marco’s, and Marco is utterly destroyed.

St. Alban the Hospitable

Back to St. Alban. He was a virtuous pagan, rich in philoxenia. A poor man sought shelter with him. Alban knew the man was a Christian priest, but that didn’t matter. He was a man needing shelter, so Alban sheltered him. It’s not clear how long – but long enough that, over many meals and many conversations, Alban came to admire him and his blameless life and his devotion to the God he served. Alban made himself a disciple, and the priest made him a Christian.

But people talk, and soon word of Alban’s unusual house guest reached the ears of the governor of Verulamium. The governor sent soldiers to arrest the priest. Alban learned what was about to happen, and he insisted that his guest exchange clothes with him and depart. When the soldiers arrived, they arrested their supposed priest and took him to the governor.

The governor wasn’t pleased. He ordered Alban to sacrifice to the gods or die.

St. Alban refused.

A judge interrogated him. Alban wouldn’t tell him much. He acknowledged being a Christian. He gave his name. And he finally said that he wouldn’t worship the gods (whom he called devils). Instead, he said, “I worship and adore the true and living God who created all things.”

These words, I have read, are used to this day in prayer at St Alban’s Abbey.

The judge, not knowing the future, urged Alban at length to change his mind. When entreaties were useless, he had Alban scourged, thinking the pain would diminish his commitment. It didn’t. Alban was steadfast in his faith.

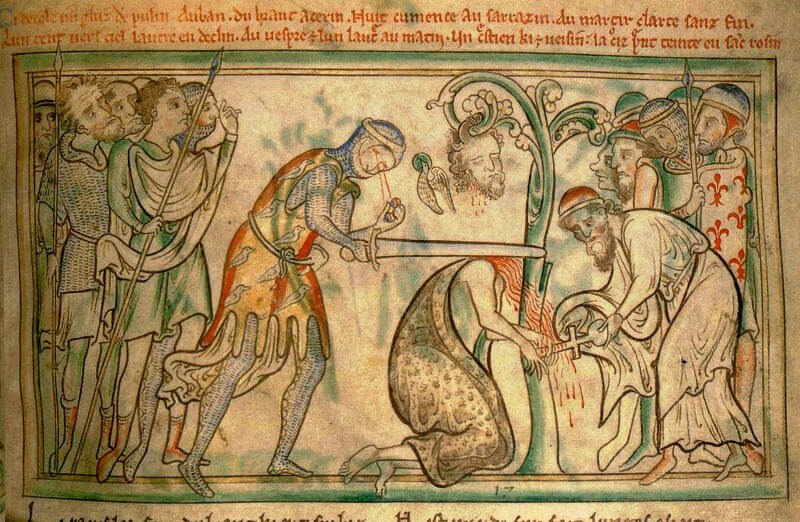

So the judge ordered him to be beheaded.

The Death of St. Alban

Executions at the time functioned as a kind of public entertainment. Everyone went to see an execution then, much as people today go see a movie. The execution ground, as it happened, was on the other side of a river from St. Alban’s home, and such a crowd had gathered that Alban and the guards and the executioner couldn’t get to the bridge, much less cross it. They camped on the near side of the bridge for the night. The next morning, St. Alban walked to the water, and the river dried up so they could cross on dry land.

This terrified one of the executioners. He threw down his sword and refused to have anything to do with the death of Alban. Another man was drafted for the duty. When that man killed both St. Alban and the executioner, the stories say, his eyes refused to look on what he’d done, and came out of his head.

From that day to this, St. Alban, the protomartyr of Britain, has been considered the patron of refugees and victims of torture. And, as it happens, while St. Alban’s Day is kept on June 22, it has been in some places kept on June 20 (a result of a scribe’s error). And June 20 every year is World Refugee Day.

Resources

If you’re looking for picture books that explore the refugee experience, I’ve got a couple of book lists that might interest you. This list from Patricia Nozell provides synopses of the stories with links to full reviews. Mia Wenjen offers a list of books with synopses. Her list includes not only picture books but books for older kids as well.

Prayers

Here is the troparion to St. Alban, as sung at St. Nicholas the Wonderworker Orthodox Church, Oxford, England:

Thou didst defend the persecuted priest, and thyself didst receive the message of salvation.

Fearless before the judge thou didst proclaim:

“My name is Alban and I serve the true and living God.”

Thou didst become the first-fruit of our land;

O holy martyr Alban pray unceasingly to God for the salvation of the world.

The OCA uses different troparion for St. Alban. There is also a prayer to St. Alban for refugees that is not specifically Orthodox, but which you might find helpful in your devotions.

Read More

A table where strangers are welcome: Philoxenia calls us to open the door to other people, and to welcome them to the table.

Silent as a Stone: A Review: This picture book by the late Jim Forest tells the story of one incident from the life of St. Maria of Paris. When the Nazis were holding Jews in the Velodrome in Paris, she smuggled the children away.

The Grace of Being There: Stories of saints and single moms: I contributed one of the essays in this remarkable collection, which explores the relationship between saints who were single moms and the lives of single moms and their children.

Buy the Books!

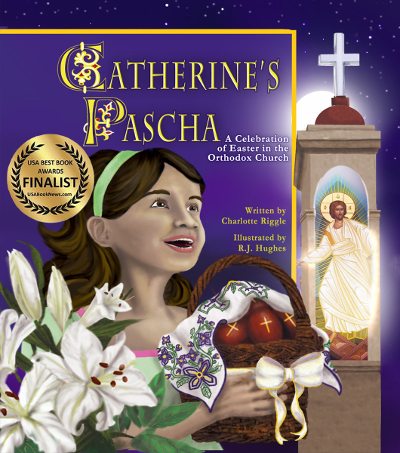

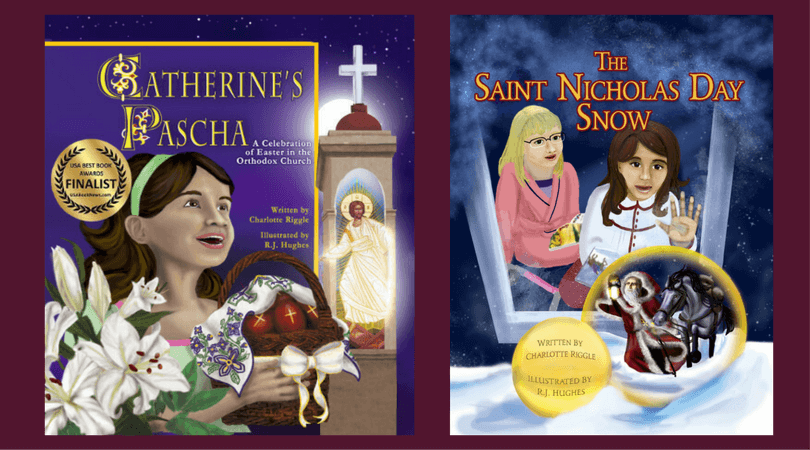

These delightfully diverse books provide disability representation (Elizabeth, one of the main characters, is an ambulatory wheelchair user). They also give Orthodox Christian children the rare opportunity to see themselves in books, and children who are not Orthodox the chance to see cultural practices they may not be familiar with.

Catherine’s Pascha

FINALIST IN THE 2015 USA BEST BOOK AWARDS

Catherine doesn’t like vegetables. She doesn’t like naps, and she doesn’t like it when her mom combs her hair. She loves hot dogs, chocolate cake, and her best friend, Elizabeth. Most of all, she loves Pascha! Pascha, the Orthodox Christian Easter, is celebrated in the middle of the night, with processions and candles and bells and singing. And Catherine insists that she’s not a bit sleepy.

Celebrate the joy of Pascha through the magic of a book: Catherine’s Pascha. Available on Amazon, Bookshop.org, and my webstore.

The Saint Nicholas Day Snow

Shoes or stockings? Horse or sleigh? Does St. Nicholas visit on December 6 or on Christmas Eve? Will a little girl’s prayer be answered? When Elizabeth has to stay at Catherine’s house, she’s worried about her grandmother, and worried that St. Nicholas won’t find her. The grownups, though, are worried about snow.

Celebrate the wonder of St. Nicholas Day through the magic of a book: The Saint Nicholas Day Snow. Available on Amazon, Bookshop.org, or my webstore.

Post updated 6/9/2021