For a thousand years, from the fifth century until the late 16th century, the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus was one of the most popular saint stories. It was told, not just among the Orthodox, but among the Monophysites and Nestorians and even among the Muslims. And everyone believed it had happened just as the story said.

In 1633, John Donne published his poem, “The Good Morrow.” The poem refers to the “seven sleepers’ den,” a reference that didn’t need a footnote in 1633. Everyone knew the story. But some few years before Donne was writing his poem, Cardinal Caesar Baronius had called the story apocryphal. And (at least in the West) few people believed it any longer.

Over time, the story of the seven sleepers fell out of people’s memory. Like the story of St. Nicholas and the boys in the pickle barrel, it seemed too silly to be believed. The theme of the sleepers shows up in other stories, like Rip Van Winkle. But since the Enlightenment, people don’t believe it any more.

Not even Christians, whose faith is founded on the virgin birth of the God-man who died and was raised from the dead. And that’s important to the story of the Seven Sleepers.

So what is the story?

The Seven Sleepers of Ephesus

It was about the year 250. Decius was emperor, and he was trying to stamp out the Christian faith, which was disrupting his empire. Seven young men in Ephesus were denounced as Christians. Their names have come down to us as Maximilian, Jamblichus, Martin, John, Dionysius, Antonius, and Constantine. (Although there are other versions of their names. In the West, they were usually remembered as Maximianus, Malchus, Martinianus, Joannes, Dionysius, Serapion, and Constantinus.)

Decius, for some reason, took pity on them, and gave them some time to reconsider and renounce their faith. They gave away all their possessions to the poor, and withdrew to a cave to pray and fast and prepare for martyrdom. When the emperor called for them to appear before him, they were found asleep in the cave. The emperor decided they weren’t going to recant. So he ordered his servants to seal the mouth of the cave. The seven Christians were left to die of hunger and thirst.

The sleepers awake

Outside the cave, time went on. By the beginning of the fifth century, the world had changed. Ephesus was a Christian city. Theodosius II was emperor. And the man who owned the land that the cave was on decided to open the cave and use it as a cattle pen.

When the cave was opened, Maximilian and his friends woke up. They thought they’d been asleep for perhaps a day. They decided that Dionysius would slip into the city and buy a loaf of bread for them to share before they died.

In the city, the merchants weren’t quick to accept the old coin. Dionysius was hauled before a magistrate. The bishop got involved. (Most likely this was Bishop Basil of Ephesus, who died in 443, although it may have been his predecessor.)

The bishop was spending much of his time dealing with one of the heresies espoused by followers of Origen. They claimed that there was no physical resurrection, that the dead would not rise. Dionysius’s story was, perhaps a welcome diversion.

At any rate, Dionysius seemed to be genuinely confused by conditions in the city. And the bishop was confused by his story. But at last the bishop walked with him to the cave. All the young men told the same story.

The bishop sent for the emperor. Theodosius came, and heard the story from the Seven Sleepers. He and the bishop accepted the story as proof of the resurrection of the dead. And the young men fell asleep once more, this time in the sleep of death.

The story in brick and ink

Emperor Theodosius ordered that the bodies of the Seven Sleepers be placed in jeweled coffins, and that a church be built over the cave. The young men appeared to him in a dream, though, and said they didn’t want the jeweled coffins. They just wanted their bodies to be left in the cave.

So the coffins weren’t made, but the church was. The cave itself was lined with brick. There were niches on the sides, and an apse in the back. It was adorned with marble and mosaics. The church was completed during the middle part of the fifth century, shortly after the death of Bishop Basil of Ephesus.

Almost at once, the cave became a place of pilgrimage. It seems that it was customary for pilgrims to leave a lamp in the church as an offering. Thousands of such lamps have been found as archaeologists excavated and dated the church.

Early accounts of the Seven Sleepers

The first written account of the miracle of the Seven Sleepers was recorded by Bishop Stephen of Ephesus, around the year 450. He was the bishop when these events occurred, although his account is now lost. The earliest account that survives was recorded by a Syriac bishop, Jacob of Sarugh, around or perhaps a bit after the year 474.

In the late fifth century and early sixth century, many other writers picked up the story. The Monophysite bishop, Zachariah of Mytilene, included it in his Ecclesiastical History sometime around the turn of the sixth century.

In the early sixth century, the story appears in the writings of Bishop John of Ephesus, Theodosius the Pilgrim, and a Latin deacon named Theodosius. Gregory of Tours wrote about it. In the early seventh century, the story was recorded in the Koran. (The Koran is uncertain of the number of men who slept. But it says they had a dog with them.)

For over a thousand years, no one doubted that the story was true.

Modern sensibilities

The story is no longer well known. And those who know it doubt its veracity. We live in an age of empiricists. We’re not comfortable with the idea that people might sleep for hundreds of years. We aren’t willing to suspend our disbelief.

But there’s no doubt what the people of Ephesus believed. They believed that seven men had gone to sleep during the reign of Decius, and had been awakened in the reign of Theodosius. The church and the writings tell us that.

Of course, the church and the writings don’t tell us that what the Ephesians believed was true. They could have been victims of a hoax or fraud.

Is it possible that the Seven Sleepers actually slept for hundreds of years, woke, told their story, and died? It seems possible to me. When we recite the Creed, we say that we believe things that seem far stranger than this.

Interestingly, though, the Troparion doesn’t say that they slept. It says that they were incorrupt after death and rose from the dead. Is that more likely than a sleep of hundreds of years? I don’t know.

But it seems certain that something important happened in Ephesus around the year 450. Something that defeated a heresy. Something that confirmed people’s faith in the Resurrection of Christ.

It seems, on that basis alone, that the Seven Sleepers is a story worth knowing.

Troparion

The Seven Holy Youths renounced the perishing comforts of this world,

Preferring the eternal things of Heaven.

They were incorrupt after death and rose from the dead and buried the snares of the devils!

O Faithful, let us then honor them, singing a hymn of praise to Christ!

Read More

Saint George and the Dragon: A Review: Jim Forest’s retelling of this well known story harks back to the earliest sources.

The White Cat and the Monk: A Review: This lovely picture book is based on a poem written by an Irish monk in the eighth century.

The Emerald of God, St. Euphrosyne of Alexandria: St. Euphrosyne, a fifth century saint, did not want to marry the man her father had picked out for her. In fact, she did not want to marry at all.

John Sanidopolous, in his Mystagogy Resource Center, provides more details about the story of the Seven Sleepers. You can also find more at NewAdvent.org and Wikipedia.

Buy the Books!

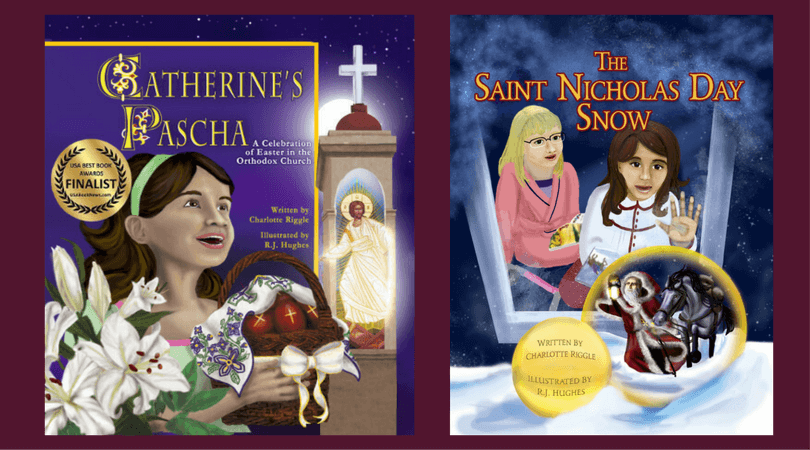

These delightfully diverse books provide disability representation (Elizabeth, one of the main characters, is an ambulatory wheelchair user). They also give Orthodox Christian children the rare opportunity to see themselves in books, and children who are not Orthodox the chance to see cultural practices they may not be familiar with.

Catherine’s Pascha

FINALIST IN THE 2015 USA BEST BOOK AWARDS

Catherine doesn’t like vegetables. She doesn’t like naps. She doesn’t like it when her mom combs her hair. She loves hot dogs, chocolate cake, and her best friend, Elizabeth. Most of all, she loves Pascha! Pascha, the Orthodox Christian Easter, is celebrated in the middle of the night, with processions and candles and bells and singing. And Catherine insists that she’s not a bit sleepy.

Celebrate the joy of Pascha through the magic of a book: Catherine’s Pascha. Available on Amazon, Bookshop.org, and my webstore.

The Saint Nicholas Day Snow

Shoes or stockings? Horse or sleigh? Does St. Nicholas visit on December 6 or on Christmas Eve? Will a little girl’s prayer be answered? When Elizabeth has to stay at Catherine’s house, she’s worried about her grandmother, and worried that St. Nicholas won’t find her. The grownups, though, are worried about snow.

Celebrate the wonder of St. Nicholas Day through the magic of a book: The Saint Nicholas Day Snow. Available on Amazon, Bookshop.org, or my webstore.